Women‘s Equality Day, celebrating the 104th anniversary of the passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution which gave women the right to vote is August 26. In recognition of this momentous event, the Sentinel will run a series of articles about the historic, and sometimes heroic women who made Lincoln County what it is today. This series will culminate in September, with a program at Lincoln County Historical Museum that will tie a new mural to be placed in the State Capitol Building in honor of the state’s historic women to the historymaking women of Lincoln County.

August 18 is the 104th anniversary of ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment which gave women the right to vote. This is the first of a series of articles about the strength and determination of women in Lincoln County history in relation to our foundation and convictions. The series will culminate in September with the unveiling of a new mural to be placed in the State Capitol Building celebrating the historic and sometimes heroic women of Kansas. Included in this mural is Mrs. Anna Waite, an early Lincoln County settler. A program will be presented at the Lincoln County Historical Museum in conjunction with the unveiling of the mural.

To understand this movement, we should first understand the history of the issue.

During the United States’ early history, women who immigrated, homesteaded and survived the dangers of the westward movement often fought for their lives against Indigenous Americans trying to preserve their lands, hungry animals and treacherous criminals. They fought alongside their husbands, or if unmarried, fought alone. They worked hard to settle the lands west of the Mississippi yet were denied common rights enjoyed by men, facing discrimination because of their gender. Women were excluded from jobs and educational opportunities and the ownership of land. Since women did not have the right to vote (also known as suffrage), they were limited in terms of their influence over laws and policies, even while having an impact on history. Before the Civil War, many women took part in reform activities, such as the abolitionist movement and temperance leagues. They wanted to pass reform legislation to address the problems they saw in American society, but politicians would not usually listen to those who were disenfranchised (did not have the right to vote). Frustration with the low status in society, women were motivated to create a movement that culminated in the Nineteenth Amendment. This amendment says, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” That is, it prohibits discrimination in voting based on sex.

Women first organized at the national level in July of 1848, when suffragists such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott convened a meeting of over 300 people in Seneca Falls, New York. Early suffragists Martha C. Wright, Jane Hunt, and Mary McClintock, along with abolitionist Frederick Douglass attended this meeting. The delegates discussed the need for better education and employment opportunities for women, and the need for suffrage. While there, Stanton wrote the Declaration of Sentiments, which is considered to be the founding document of the women’s rights movement.

The suffrage movement grew larger in the years following the Civil War. Women across the United States, including Kansas women, participated in the effort even though they didn’t always agree on strategy. Suffrage organizations were formed to carry out a variety of tactics. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and her longtime collaborator, Susan B. Anthony, founded the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). The NWSA focused on changing federal law and opposed the Fifteenth Amendment, which protected Black men’s right to vote but excluded women. Several people, including Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe, disagreed with Stanton and Anthony’s position on the Fifteenth Amendment, and formed a new organization: the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). AWSA supported the Fifteenth Amendment, and its members were both Black and white.

Because neither of these organizations reflected the experiences of all women, working class women and/or women of color often experienced discrimination not only because they were women, but also due to their class and race. Leading reformers including Harriet Tubman, Frances E.W. Harper, Ida B. Wells and Mary Church Terrell created the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC) in 1896 to campaign in favor of women’s suffrage and improved educational opportunities, also fighting against Jim Crow Laws, which were a collection of state and local statutes legalizing racial discrimination. These laws remained in effect for 100 years – until 1968, marginalizing African Americans.

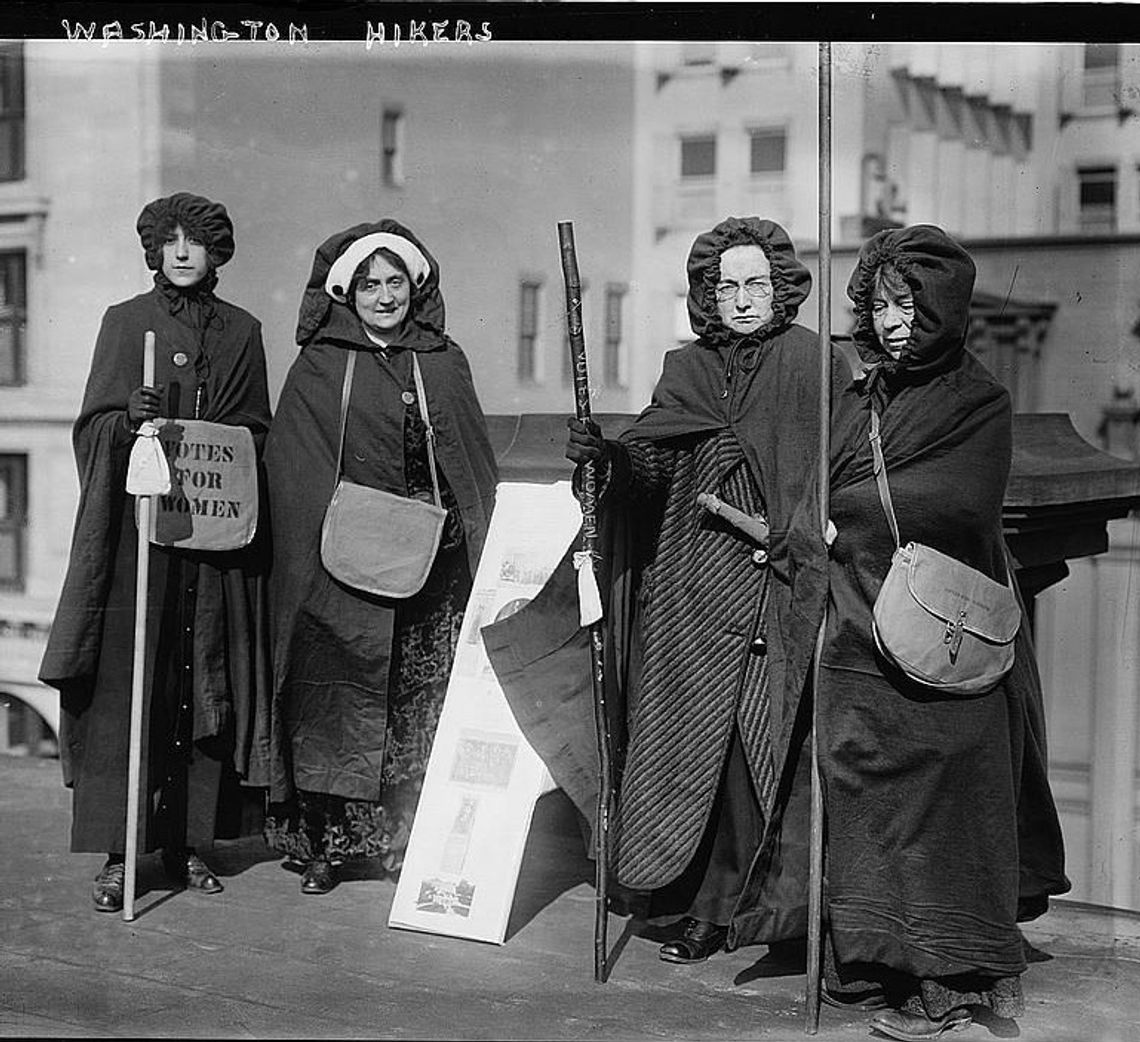

In 1890, Anthony helped merge the NWSA and AWSA to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Member Alice Paul, thought the organization was too moderate, founding the National Women’s Party (NWP) in response. The NWP had a variety of strategies to bring attention to the suffrage movement. Its members picketed the White House and held demonstrations in nearby Lafayette Park and at the U.S. Capitol and Senate office buildings. They took part in lobbying, nonviolent protests, hunger strikes, civil disobedience, and silent vigils. Street speaking, pageants, and parades were some of their more eyecatching actions. Alice Paul organized the largest suffrage pageant, which took place in Washington, D.C. on March 3, 1913. About eight thousand women marched from the Capitol to the White House, carrying banners and escorting floats. Up to 500,000 spectators, in support or opposing, watched the march. Others harassed and attacked suffragists in the parade; over 100 women were hospitalized with injuries that day. The parade was important in the movement, not only due to size, but for the challenge of traditional ideas of how women should behave in public. They were loud, bold, and theatrical. Those who opposed women’s suffrage feared that society would suffer if women played a role besides wife or mother. That opposition was eventually overruled.

In 1919, both the House of Representatives and the Senate passed the Nineteenth Amendment. The amendment then went to the states for ratification. Thirty-six states needed to ratify the amendment in order for it to be adopted. On August 18, 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States went into effect.

On November 2 of that year, more than eight million women voted in the national election for the first time. Women also ran for office in greater numbers. Jeanette Rankin was one of the few women to hold an office before the ratification of the amendment, and when elected to Congress in 1916 she said, “I may be the first woman member of Congress, but I won’t be the last.”

Women in Lincoln County and throughout Kansas worked hard to make the passage of the amendment a reality. Anna Wait, an early Lincoln teacher and co-owner of the Lincoln Beacon, was instrumental in gaining a woman’s right to vote. Due to the efforts of these women, Kansas ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on June 19, 1919, becoming one of the first states to do so.

Next week: More on Anna Wait